Tony Hillerman is something of an institution among contemporary Southwestern novelists, and while he was admittedly a writer of limited range, he captures the feel of Navajo country and aspects of the difficulty of living simultaneously in an ancient culture and a modern culture. He's probably best known for his "Leaphorn and Chee" novels, eighteen books centered around two Navajo police investigators. While it isn't fair to say that if you've read one you've read them all, they mostly follow a pattern: one or more murders in Navajo Country, investigation by Leaphorn, Chee, or both, discussion of elements of Navajo culture or religion, and comments on the difficulties of living in Navajo Country. The books follow in sequence, and while there are continuing stories regarding Leaphorn's aging and retirement and Chee's love life and struggle to define himself as either a modern Navajo or a traditional Navajo, the books are not closely linked: while there are characters who recur they can typically be understood in single novels.

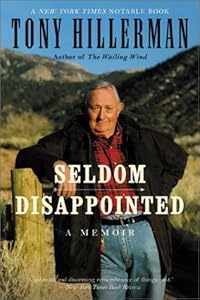

In addition to these Hillerman wrote a couple of novels outside the series and several nonfiction books including a memoir, Seldom Disappointed.

While I can usually read a Hillerman novel in two sittings, Seldom Disappointed is a more thoughtful, denser read. I'm only a quarter of the way through, and I'll be pleasantly surprised if I finish this book this week.

Hillerman grew up in Catholic in Oklahoma and Indian Territory during the Depression, then fought Germans in World War II in Europe, and I'm just to the point where he has shipped off for Europe. I am beginning to suspect that Hillerman's voice in his nonfiction is freer, smarter, and better than in his novels: his descriptions of frontier education between the wars, of Benedictine missions in Indian country, of what his family's Catholicism meant and implied about them, of realizing that he wasn't college material, of marginal poverty, even of the practice and perception of hitchhiking during World War II are carefully considered and surprisingly economical. His use of digression and foreshadowing is balanced and well-considered. I'm really impressed with this book, and I think it would make for good reading for anyone considering writing a memoir.

In addition to these Hillerman wrote a couple of novels outside the series and several nonfiction books including a memoir, Seldom Disappointed.

While I can usually read a Hillerman novel in two sittings, Seldom Disappointed is a more thoughtful, denser read. I'm only a quarter of the way through, and I'll be pleasantly surprised if I finish this book this week.

Hillerman grew up in Catholic in Oklahoma and Indian Territory during the Depression, then fought Germans in World War II in Europe, and I'm just to the point where he has shipped off for Europe. I am beginning to suspect that Hillerman's voice in his nonfiction is freer, smarter, and better than in his novels: his descriptions of frontier education between the wars, of Benedictine missions in Indian country, of what his family's Catholicism meant and implied about them, of realizing that he wasn't college material, of marginal poverty, even of the practice and perception of hitchhiking during World War II are carefully considered and surprisingly economical. His use of digression and foreshadowing is balanced and well-considered. I'm really impressed with this book, and I think it would make for good reading for anyone considering writing a memoir.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=2c512d1a-6570-8909-a293-dbb354dc42fc)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=19a2f3cf-9b04-4695-ac56-6a3c4c4a8a2e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a15989a5-1cfd-4a80-96f7-0ac2df80ffb7)